A reader's response to materials presented for EN398, spring semester.

Monday, February 28, 2011

A "quaint modern American fatalism"

While reading Silas Lapham, one phrase stuck out to me and sort of followed me through to the end. Chapter 9 ends with a discussion between Mrs. Lapham and her daughter, Penelope. They discuss Irene's relationship with Mr. Corey, who may or may not be seeking her hand in marriage. In frustration, the two bemoan having ever met the Corey family, and wish that they had never become involved with the paint business. Finally, the two recognize that the situation is out of their hands.

"Well, we must stand it, anyway," said Mrs. Lapham, with the grim antique Yankee submission.

"Oh yes, we've got to stand it," said Penelope, with the quaint modern American fatalism.

I found these two descriptions to be so compelling, the "grim antique Yankee submission", and moreso the "quaint modern American fatalism". Submission and fatalism, both terms that imply a lack of control. However, Mrs. Lapham serves as a representation of an older America, and her approach to these events is one of passivity and submission to dominance. She recognizes the situation as being out of her control and pessimistically admits defeat.

However, Pen, who to me represents the hope for new money families to survive in upper crust society, approaches the situation with fatalism. Fatalism, or the philosophy that events are out of one's control and left instead to fate, could certainly characterize the lower class. However, rather than the expressly negative view offered by Mrs. Lapham's submission, fatalism suggests that while we are powerless, fate can decide both negative and positive paths for us. While Mrs. Lapham sees the glass as half empty, Pen just sees that there is a glass, for better or for worse.

I feel like this submissive vs. fatalist philosophy fits in very well to much of what we've been discussing in class structure. Is it possible to move up in class, or are we born to submit with our preexisting dominated social status? Is social mobility even something that can be influenced by one's actions, or is it left up to fate? We see that Silas's rise to economic power was by the good fortune of finding the paint well on his father's property. While his rise also entailed a good deal of hard work, the initial push was from the chance discovery of a great fortune buried beneath a giant tree. Could Silas have risen economically if pulling himself up by his bootstraps alone? And once he rose economically, could he ever assimilate socially? Or was he and the rest of the Lapham family fated to forever linger on the lower crust?

Saturday, February 26, 2011

Reflection and Disbelief While Reading Silas Lapham

While reading Howells The Rise of Silas Lapham, I had a moment when I realized that I wasn't taking a word of the book seriously. It was like Howells was talking about all these characters and storylines and I was just tuning out, falling asleep in the middle of lecture. I felt instantly shamed and self-conscious about this state of mind and took a minute to step back and take stock of what I was feeling. It all came together for me in my Fiction Writing class with Professor Boylan, when we had a brief discussion of character and plot believability. The willing suspension of disbelief, the moment when we, as readers, say "okay, yeah, I'll buy this, I'll see where you take this". I realized that I didn't believe a word of this story, I didn't believe in Silas's paint or Pen's sassiness or the Corey family's gradual moral decay. I didn't believe any of it-- to me, it felt like a caricature of the upper crust.

With this in mind, I connected strongly with Leah's blog in which she describes the very in-your-face attitude of richness and new money. Leah argued at the end that "no matter what occurs, the standard which is used to measure social status will always be obnoxious, whether it's based on family history or how much money you spent on a car that you don't drive but leave in the drive-way for everyone to see." I thought this was completely spot-on to how I was feeling. It was obnoxious to me, all of it. I was especially annoyed by the Corey family's social pretension, their exaggerated commitment to social hierarchy and the superiority afforded to them by their "old money" status. And then Silas's own garish over-decoration of his house, and the intense social structure and immobility displayed in the dinner party...

Overall, I felt that Silas took an almost satirical hit at class division and social structure, and if there's one thing that gets old fast for me in literature, it's satire. Of course, I'm not positive. I tried to find facts and information online to support or refute this claim and didn't get anything solid. It could actually be a fairly accurate of American culture and class structure during the 1800s. However, I didn't buy it. To me, the view of old rich in America felt forced, overdone, and exaggerated. Anyone else in my boat? Or did you feel like Howells did an historically accurate job? Was that even what he was aiming for with Silas?

Sunday, February 13, 2011

Life Satisfaction, Yesterday and Today

I found this article in Time magazine that discusses the idea of money buying happiness. Its big claim is that happiness today is positively correlated with an annual income up to $75,000-- after that point, happiness plateaus. Life satisfaction, or the feeling that one’s life is working out as a whole, continues to increase, but the subjects surveyed showed no significant increases in happiness (or unhappiness, for that matter) after that point.

I found this to be very interesting, and perhaps in contrast with Twain’s The 30,000 Bequest. Aleck and Sally seemed to become increasingly distressed and unhappy as their wealth increased. With the added power and responsibility that their imaginary funds afforded them, the two felt more pressure to invest wisely, more awareness of the immense possibility of their success and disaster of their failure.

However, the point of the article that really drew me was the mention of “life satisfaction”, and how it continues to increase as individuals become more wealthy. I saw quite the opposite in Sally and Aleck’s story. It seemed that as their funds increased, they became more and more dissatisfied, more aware of not only how much money they had, but how much others had as well. The more imaginary money they gained, the more they put themselves in the context of high-society.

I’m kind of curious about the discrepancy between Sally and Aleck’s life satisfaction and the modern trend of life satisfaction. What about modern society allows us to feel more and more satisfied as we gain money, whereas Twain depicts an America that becomes more resentful towards their lives and work as they earn more?

"Vast wealth is a snare"

In class, we mentioned the concept of “true happiness” in Twain’s The 30,000 Bequest, whether it was present or even possible in the story. Aleck and Sally view money and riches as a route to happiness. On this thought, I did a text search and traced the word “happy” through the reading.

The first instance in the first chapter describes Aleck and her position in life: “She had an independent income from safe investments of about a hundred dollars a year; her children were growing in years and grace; and she was a pleased and happy woman. Happy in her husband, happy in her children, and the husband and the children were happy in her.” This sort of happiness centers around family bonds, around the security of her “safe investment”, but even more so the security she receives from having happy and healthy children. Shortly after this exposition, Aleck praises Sally for a smart investment move and he is said to be “poignantly happy”. However, this show of joy is based around the positive interaction with his wife, not necessarily for the money.

The next mention of happiness does not come until a few chapters later. It is, interestingly enough, during another instance in which Aleck is especially proud of Sally, and expresses her satisfaction with his latest investment with “a prideful toss of her happy head”. There is another instance of the word in a later interaction between the two, and then the mention of being “happy” thins out.

When Sally learns that a recent move has given them an immense lot of disposable income, he is described as being “happy beyond the power of speech”, but in the following paragraph is noted to be “crumbling”. This sort of “happiness” is crippling them. And later, the description of Aleck as “flattered and happy” is bordered by depictions of a Sally that is “bleary”, “fervent”, and “dizzy”. The couple does not sound truly content and stable-- they sound ill.

The final interesting cluster of the word comes when Sally and Aleck believe that they have secured marriages with their two daughters to wealthy men of royalty. Sally is “profoundly happy”, but it is not because of any wealth that they marriages may add to their capital. Her happiness stems from the security of her daughters, from the joy that a parent feels in providing for and protecting her children.

One of Sally’s last quotes really drives home the point of wealth as false happiness, as he muses “Vast wealth, acquired by sudden and unwholesome means, is a snare. It did us no good, transient were its feverish pleasures; yet for its sake we threw away our sweet and simple and happy life-let others take warning by us.” He acknowledges wealth as a false and consuming happiness, and regrets the simple, happy life that he lost.

I guess all this has led me to question my own views on money and happiness. Would I be satisfied with insane riches? Would I know when to stop? With all the pressure and potential that fortune offers, is true happiness even possible?

Saturday, February 12, 2011

The Girl Effect

I found the Girl Effect site through a friend working in DC for the semester. It’s a nonprofit that targets 12-year-old girls before they can fall victim to forced marriages, prostitution, and drug use. They seek to provide education and work opportunities so that girls can take charge of their lives and avoid lives of destitution and crime.

What struck me about this site in relation to Maggie was point that in the eyes of many cultures and communities, a 15-year-old girl is considered an adult woman. Old enough for marriage and childbirth, old enough to support a family. I look back on myself as a 15-year-old and am horrified by the thought of this.

It was interesting though, to see how Maggie tried to put on the pretenses of being an adult woman. We discussed the “nesting” tendencies made impossible by the tenements that she attempted anyways with her wall decoration. Amidst her brother’s violence and mother’s disorderly drunkenness, she seems the only organized and possibly parental figure in the picture. However, in her incredibly naive approach to Pete, we see that she is indeed just a girl and nowhere near mature enough to handle her situation. I feel like this contrast of the expectations placed on her and the reality of her abilities only adds to the overall sense of tragedy.

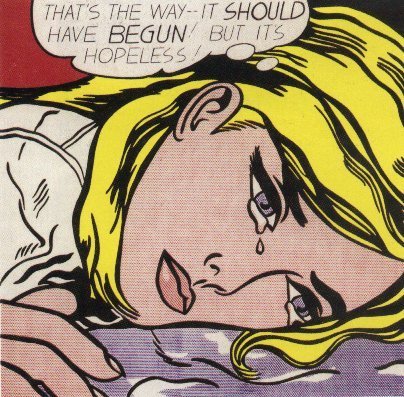

Powerlessness and Hopelessness in Maggie

In our class discussion on the presentation of poverty in Stephen Crane’s Maggie: A Girl of the Streets, I was particularly stuck on the idea of “hopelessness”-- in Maggie’s situation, and in the situation of the tenement housing overall. I skimmed back through the novella and tried to identify points where Maggie may have been able to make a turn for the better, to follow a brighter, more hopeful path. Sure enough, I couldn’t find anything. I became frustrated by her lack of mobility, almost annoyed by her simple naiveté towards Pete and shameful return to her family. Yet despite Maggie’s failings as a character, I couldn’t dislike her.

I realized on this second read-through that my biggest problem was not with Maggie’s character; it was with the situation overall. Because of external factors in her environment-- lack of education, extreme poverty, disturbed family structure, and violence-- she was driven towards the “saving grace” that Pete seemed to represent. It was no failing on her part that she should end up in that eerie final section, prostitution herself to strangers passing by. Crane seems to place the blame for Maggie’s demise entirely on external factors. Maggie makes few choices for herself, but the ones she does make are driven by societal failings, not any avoidable error on her part.

I do have one question, though. Crane seems to construct Maggie as a vehicle of pity, a dramatic example of a pure young woman destroyed by her terrible environment. However, Maggie’s final actions are prostitution and subsequent suicide, both of which typify immorality and sin. How does he hope to have Maggie draw on the audience’s pity and sympathy if she ultimately assimilates into the immorality exemplified in the social and economic environment that brought her down?

Subscribe to:

Posts (Atom)